History of St. Dominick – an occasional series: #5 Pre-history – 1485 Map 1: Part 4 Roman - Dark Ages: Indract & Dominica

History of St. Dominick – an occasional series: #5

Pre-history

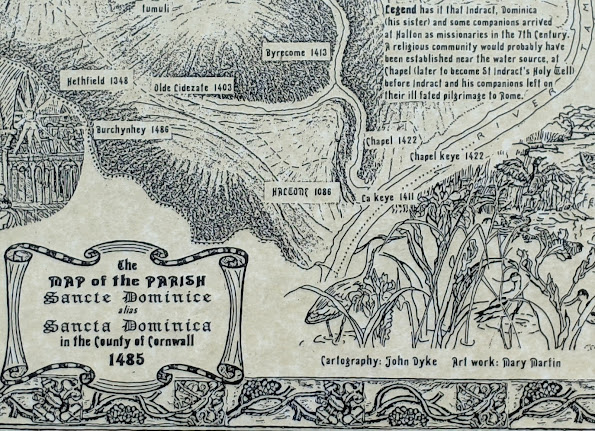

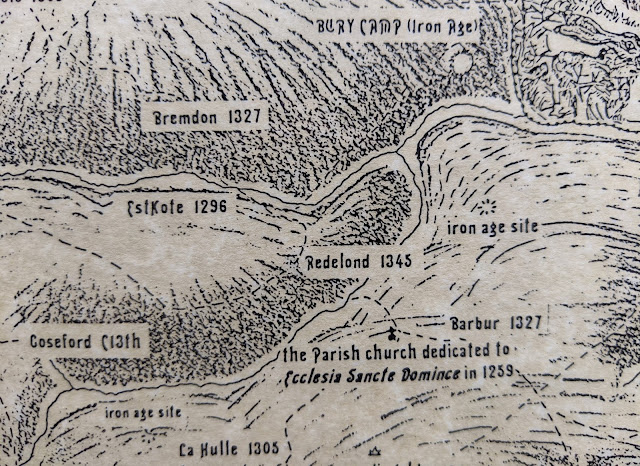

– 1485 Map 1: Part 4 Romans to the Dark Ages and Indract and

Dominica

Part 4 (Romans AD 43 - AD410 Dark Ages 410 - 1066)Boldly stating Roman in this title suggests we have something Roman in St. Dominick. However, as far as I know we do not have any Roman remains … not even a few Roman coins turned up by metal-detectorists - unless someone can tell me different!

I would not be surprised if something Roman was to be found somewhere in the Parish however, after all we border the Parish of Calstock and it isn’t far by river to the settlement at Calstock – and we now know there was a substantial Roman Fort in Calstock. This was only discovered, near St. Andrews Church on the hill above the town, in 2007. (Reference 1) I had the pleasure of joining in a community dig there in 2019 – more opportunities will be coming up as the dig area expands and the funding continues.

This Roman Fort appears to have been in use between AD 43 and 100 – and probably concerned with the mining workings in the area at the time (most probably open cast in trenches called gunnis) and with securing the access by river; as the forts further down Cornwall on the upper navigable reaches of those rivers seem to be.

Having dealt with the lack of evidence for Roman intervention in our parish area, I will say that the usual iron-Age life probably carried on as in pre-Roman times, though there is evidence in other parts of Cornwall for a slight change in house shape – from round to oval, no hard evidence is available for either in our parish area.

Bad Weather

In the mid to late 500s the weather turned very bad. We know this from the few written records that exist – but it is amazing that, such is our technology now, that we can tell the weather patterns from these times quite accurately from studies of the soil, tree-rings and ice-cores. 535 – 536 saw the result of, most probably, a huge volcanic eruption – throwing a vast mass of particles into the atmosphere that, for at least 18 months, the sun was not bright enough in the daytime to cast a shadow. (REF 2)

This resulted in deeply cold winters and failed crops over the summers. There was snow reported in the summer months in China, and frosts before harvest could be gathered in in Italy. This affected nearly the whole world – and it seems it was a trigger for a climate shift, persisting with colder years for about a century - and in the years following the initial disturbance - unprecedented storms and flooding are noted in the chronicles – and in countries like Norway, the inability to grow wheat where previously it has been a successful crop.

The Justinian Plague

All this contributed to wide-spread famines – which it is fair to assume the people of this area suffered along with the rest. Then, just when people were at their weakest, a version of the bubonic plague started sweeping across what was left of the Roman Empire and beyond. Named after the Emperor of the time – the Justinian plague arrived in Constantinople in AD 542, having started in the outer provinces, probably Egypt. It raged through the empire and beyond, but did not go away completely for the next 200 years, sporadically spreading in waves across countries following trade-routes and military exploits.

All in all, it is estimated that 25% - 50% of the population of the empire died from this pandemic – around 100 – 200 million people – and, with the Cornish trade with the rest of the world especially in tin, it is likely that Cornwall was affected too. It is only relatively recently that reports of ‘pestilence’ in Britain during this time have been confirmed by archaeology and genome sequencing to actually have been reports of break-outs of the Justinian Plague in Britain. (REF: 3)

However, these were known as the ‘Dark Ages’ partly due to the lack of records kept or documents written – so whether our particular area was affected badly or not, we will never really know – but we do know that they were literally, as well as figuratively, dark times.

Photo of tower window

Now into this I will drop the legends of Indract and Dominica – as they fall perfectly into this Early Medieval Period (as the ‘Dark Ages’ is now known).

Legend has it … even I begin to write about Dominica and Indract this way – ‘Legend has it …’ but I have been wondering if this is helpful. Legend is a strange word – to some it suggests that the next bit you will see written is ‘made-up’ or at the very least, ‘highly exaggerated’ and not ‘proper history’.

Well, let’s have a look at this ‘legend’ of Saint Dominica and Saint Indract. There are actually three parts to the legend, with only the ‘middle part’ referring to here; this particular area.

The first part ‘belongs’ to Tamerton Foliot’ – further down on the other side of the river. This says that Indract, Dominica (son and daughter of an Irish King) and nine companions arrived there (at Tamarunta) from Ireland around AD689. Indract stuck his staff into the ground and it sprouted into an oak tree, he founded a church there and made ponds that always had fish in them.

The second is ‘ours’ that, Indract and Dominica, son and daughter of an Irish King, came further up the Tamar, also in AD 689, landing near what we now know as Halton Quay, and made a religious settlement here.

The third 'belongs' to a church which does not exist now, as it burned down in the 12th century, but was known, even then, as ‘the Old Church’ and was situated within the site of what is now the remains of the Abbey at Glastonbury.

This 'legend' from the martyrology: Indract and seven (some versions say several) companions went on a pilgrimage to Rome. On their way back they decided to visit the tomb of St. Patrick (which was in this church) – and after this they camped for the night nearby at a place recorded as ‘Hywsic’ – which may have been a place about 5 miles away known as ‘Huish episcopi’.

King Ine – King of Wessex was staying nearby at as place called ‘Pedred’. A Thegn named Husa (a high-up serving warrior of the King) and his men came across the monks and, believing the polished brass tips on their staffs to be gold and the bulging scrips (leather bags) they carried to be full of valuables, came back later when they were asleep and murdered them all. Afterwards they hastily buried their bodies (which, in that terrain, may just have consisted of pushing them into the boggy ground). The scrips, it is said, contained seeds, and celery seeds are specified.

Subsequently pillars of light were seen at night, and the locals told the King what had happened. He, also witnessing the lights, had the bodies retrieved - all but one, which was never found - and buried in the basilica of the Church as martyrs. Indract was accorded a pyramid-shaped tomb to match St. Patrick’s, in the opposite aisle.

Miracles were later attributed to prayers said at this tomb – and St. Indract’s saint’s day was recorded as May 8th – his date of martyrdom.

The copies of these ‘legends’ that still exist were all were written down in the 12th and 13th centuries, in Latin – many citing they were re-writing from earlier manuscripts, some of which they said had been written in Old English, that is - Anglo Saxon, and which have not survived.

In history, the specific can make for more believable evidence, if it can help verify the account. That there are specific places and names given helps to check these accounts. We can date our Indract as plausible for his life here would coincide with the reign of King Ine – and the king being within the area from the place-names at that time. The venerable Bede, considered the greatest early historian of the English church, writes of King Ine: he was a godly man – who later abdicated so that he could spend his last years in Rome as a pilgrim. So, that he would both be horrified at this murderous act and have the monks re-buried extra respectfully, holds water.

That we are given a name for the Thegn, a high ranking person in the King’s service, would suggest that there was a record kept, maybe of a trial, now lost, that actually identified the wrongdoer and the ‘reasons’ for the attack.

And the miraculous pillars for light? Of course we now know of the cause of the ‘will-o-the-wisp or bog-lanterns’ effect - by breaking into boggy ground causing the release of methane and the phosphines that cause them to spontaneously ignite – so even this rings true.

BUT ... but .. this ‘evidence’ was written in the late 1100s, early 1200s and even the 1300s – not contemporaneously – written nearly 500, or more, years after the event. Taken that the main writer, an esteemed historian of his time and still recognised as one of the best in the world in his era, declared his information comes from an earlier manuscript written in Old English (Anglo-Saxon) does push the dating back a bit … but even so – where did it come from initially and can we believe it – knowing that sometimes the facts were twisted to make shrines more profitable in the late middle ages?

Well, records of law-courts the king held and of the king’s travel could well have been kept and could have been used. This may have provided some of those details, but it will be the oral tradition that held much of what was told intact, from the deed to the writing-down.

Now-a-days we tend to think of the oral tradition in terms of folklore – or in terms of primitive tribes where the oral tradition still runs strong and true down family lines. But the tribes show us how the oral tradition keeps the stories of their history alive, and of relationship bonds, accurate. It runs down family lines as it is an occupation, a trade or profession, to be the keeper of the oral tradition – to hold the knowledge and to be able to retell it accurately, the same, time after time, and to teach this and pass it on to the next generation of ‘story-teller’ - the father makes sure the son has it all in his head.

If this sounds far fetched let me tell you a true story about oral tradition and local memories.

Back in 1995 when I was working on the St. Dominick Parish Map Project I went along to the senior circle club meeting to talk about the project and ask those who had grown up around here {of which there were a lot in that group back then} amongst other things what the roads and lanes were called.

They had great fun telling me about the areas where they went courting – and also the origins of the a bit of lane named ‘Shetty Ford’ - but one lane, the one that starts right outside the Parish Church and runs up the hill past Trehill farm to the junction, they told me was called ‘Rill Road’.

I clarified that they weren’t saying Trehill – oh no, it was Rill road they said. (Also pointing out that those who called it ‘church lane’ were quite wrong – church lane ran from the church down the hill and up to Radland Cross) I was amazed!

Why? Because I already knew from other researches that the farm at Trehill had been called Trehill for nearly 300 years – But that before that - it was called Rill Farm – Rill Farm - the name the senior St. Dominickans knew the lane by. And this remembering was without the regular ‘story-telling’ to the ‘tribe’ or an oft-used oral tradition specifically being handed down – or even it being written on maps - because it isn’t.

So when I look at oral tradition I have great respect for it and the possibility that it remembers the truth – of things that were not written down.

Which brings us to Dominica, whose saint’s day is now the 9th of May but, incidentally, was originally the 30th of August. We know this from actual written records in 1445 - when the church of Sancti Dominica requested a change in feast day, “as it fell, inconveniently, during Harvest – to the day after St. Indract’s” (May 9th)

Prior to that we have the dedication of the church to St. Dominica in 1259. A dedication to a saint no-one except those in this area seemed to have heard of. No elaboration of a story to bring in pilgrims, just the local oral tradition of a saint in their midst. They didn’t chose St. Indract – with whom they had links and was already an acknowledged saint elsewhere, but Dominica - and a good 550 years after her being here – and this can only have come down through an oral tradition as nothing else is written about her apart from the legend of her coming here with Indract, setting up the religious settlement – and not going away.

But I am getting ahead of myself – we have the Norman invasion and the Domesday book to deal with before the church was built – that’s for the next blog post.

What are your thoughts on this section of the History?

Are you enjoying it - or is it all a bit murky and dark??

And it you have found Roman remains in the parish – do tell!!!

REF: 1) Roman Fort at Calstock

http://humanities.exeter.ac.uk/archaeology/research/projects/calstock/

REF 2) Weather chart 500 – 750 AD

https://premium.weatherweb.net/weather-in-history-500-to-750ad/

REF 3) Justinian Plague

https://www.medievalists.net/2020/11/justinian-plague-medieval-world/

source:

https://www.pnas.org/content/116/25/12363

Comments

Post a Comment